Implementing EUDR in the Soy Supply Chain: The Case of Mato Grosso

- by

- mosaix_live

- May 19, 2025

Mato Grosso is Brazil’s largest soy-producing state, responsible for roughly 27% of the country’s soybeans and about 30% of its soy exports – a critical piece of the global soy supply chain (Reuters, 2023). Soy cultivation in this region has long been associated with deforestation, making sustainability and legal compliance a central concern (WBCSD & Guidehouse, 2024).

The recently adopted EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) aims to curb global deforestation by prohibiting imports of commodities produced on land deforested after December 31, 2020, and by requiring compliance with relevant local laws. In practical terms, for Mato Grosso’s soy this means exports to the EU must be deforestation-free (post-2020) and legally produced under Brazilian law. The EUDR’s implementation timeline was even extended by 12 months to give stakeholders more time to comply (Council of the European Union, 2024), but soy exporters are already under pressure to meet these strict criteria.

In this case study, we assess Mato Grosso’s soy farms against EUDR criteria to evaluate the state’s readiness for compliance. Our analysis examines whether soy cultivation areas have avoided deforestation since 2020 and adhered to Brazilian legal requirements. We integrated multiple data sources to evaluate every major soy farm in the state for recent forest clearing and legal irregularities. This report presents the findings in an accessible way, highlighting how prepared Mato Grosso is for EUDR compliance and what challenges and opportunities lie ahead.

Methodology

Our assessment combined geospatial analysis with official data to determine which soy cultivation areas meet EUDR requirements. We gathered high-resolution data on soy planting locations and cross-referenced these with deforestation records, land registries, and protected area maps. Key datasets and tools used include:

- Official land registry data: We used Brazil’s rural land cadastre systems (SIGEF) to obtain soy farm boundaries and ownership status, identifying which soy farms are officially registered versus those that are not. This helps flag any soy plots lacking proper registration or title, since unregistered farms often indicate legal irregularities (ABIOVE & APROSOJA, 2024).

- Baseline forest cover (2020): A Global Forest Cover 2020 map (from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre) served as a baseline for remaining forest as of the EUDR cutoff date (Köhl et al., 2023). This allowed us to know which areas were forested at end of 2020, so any subsequent clearing in those areas would violate EUDR’s no-deforestation rule.

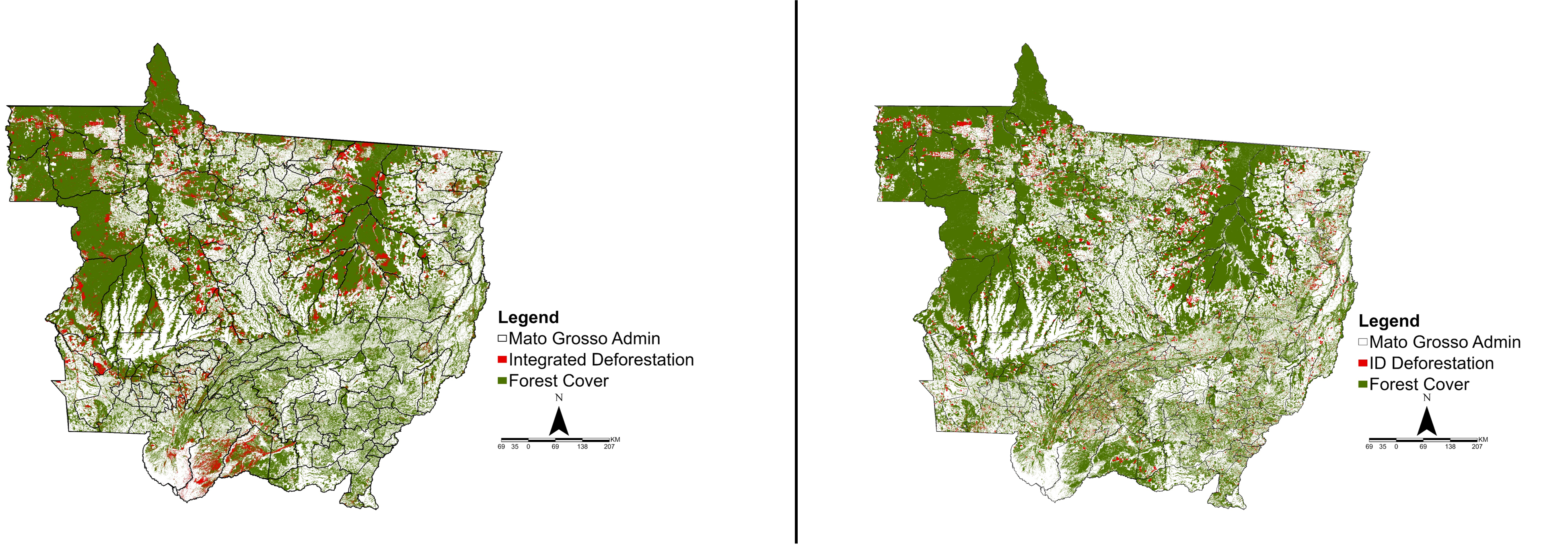

- Deforestation alerts (2021–2023): We monitored recent forest loss using integrated satellite-based deforestation alert systems, notably RADD and GLAD alerts (Landsat and Sentinel-2) for 2021–2023 (see Figure 1). These near-real-time alerts flag new clearing events across Mato Grosso’s landscapes, enabling us to detect any forest clearance that occurred after the cutoff date. Integrated alerts provide frequent updates and wide coverage to detect deforestation as it happens.

- Tropical Moist Forest Deforestation Year: This dataset was developed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC). It provides the annual records of forest loss across Mato Grosso from 2013 to 2023. It was critical for assessing long-term deforestation trends and identifying the districts most affected by forest clearance. TMF deforestation year helps visualize deforestation changes over the decade, contextualizing recent developments in land use.

- Inovasi Digital’s verified deforestation alerts: To improve accuracy, we leveraged Inovasi Digital’s Verified Deforestation Alerts (2021–2023). These are curated alerts that filter out false positives from the generic satellite alert systems and confirm genuine deforestation events. The Inovasi Digital’s- verified alerts offer superior accuracy compared to raw integrated alerts, ensuring we only count true forest loss in soy areas. This higher-quality alert data strengthens our monitoring of EUDR compliance by avoiding the noise of erroneous alerts (see Figure 1).

- Soy planted area maps: We also used Inovasi Digital’s proprietary soy planted area maps to precisely locate soy cultivation plots across Mato Grosso. This dataset allowed us to focus the analysis on actual soy-producing areas rather than broad land parcels. Using Inovasi Digital’s soy map (as opposed to more general land cover data) ensured no soy farm was overlooked and that we didn’t misidentify non-soy land as soy. It greatly increased the accuracy of our compliance checks by zeroing in on the true soy footprint in the state.

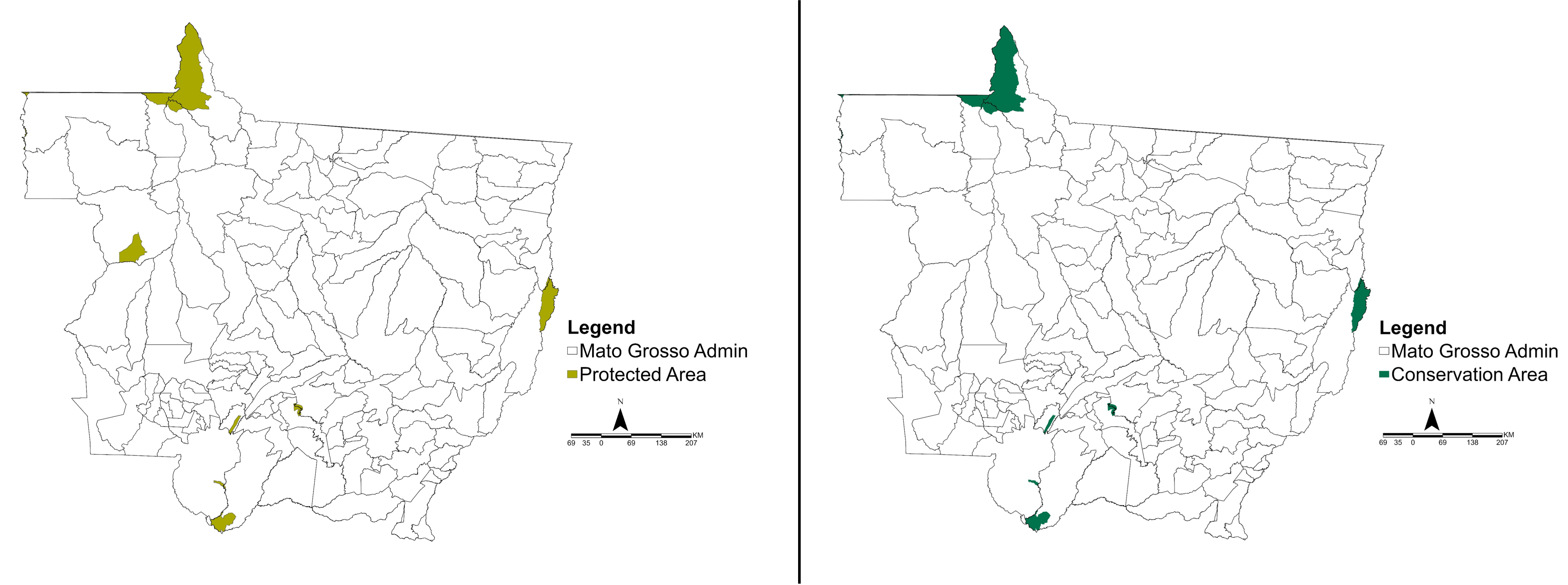

- Protected areas and public forests: We incorporated maps of protected areas, including Indigenous territories, conservation units, and Permanent Forest Reserves (public forests where agriculture is prohibited) from official sources (ICMBio, 2023) (see Figure 2). Any overlap between soy farms and these protected lands would indicate a legal violation. Identifying soy cultivation inside protected forests (so-called PRF overlaps) is crucial, since those areas would fail EUDR’s legality criterion regardless of deforestation timing.

Using these data layers, we evaluated every major soy plot in Mato Grosso against EUDR-like rules: (1) no forest clearing after 31 Dec 2020, (2) valid land tenure/registration, and (3) no farming inside protected forests. By cross-validating multiple sources (satellite alerts, official records, and Inovasi Digital’s refined data), our methodology minimized errors and provided a robust compliance status for each soy farm in the state.

Figure 1: Forest cover and deforestation alerts in Mato Grosso (2021–2023). The maps display remaining forested areas (green) and deforestation alerts (red) from both integrated alert systems (left) and ID-verified alerts (right). Extensive forest cover remains in the northern and western regions of the state. Deforestation activities are concentrated along forest edges and agricultural areas, with integrated alerts showing broader distribution and ID alerts providing refined, high-confidence detections. These visuals highlight key areas affected by land-use change and agricultural expansion.

Figure 2: Protected Areas and Conservation Units in Mato Grosso. The maps illustrate officially designated Protected Areas (left, yellow) and Federal Conservation Units (right, green) distributed across the state. These zones are legally restricted from agricultural activities, highlighting areas critical for assessing compliance with EUDR legality requirements. Data sourced from ICMBio (2023).

Results and Findings

Deforestation Trends

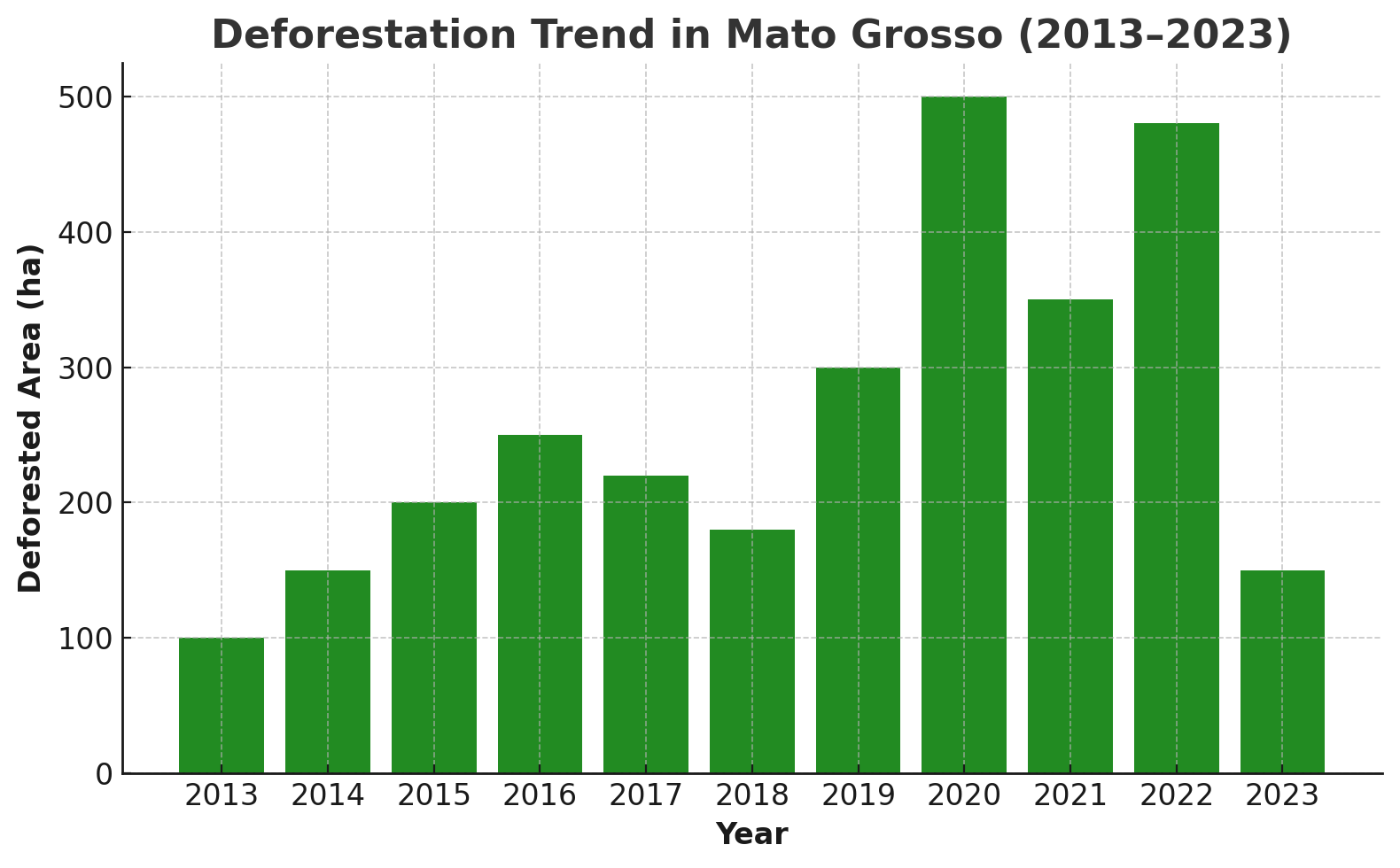

Our analysis of deforestation data (2013–2023) in Figure 3 shows that annual clearing in Mato Grosso spiked around the EUDR cutoff and then sharply declined. The state saw a peak in forest loss at nearly 500,000 hectares in 2020, one of the highest levels in the past decade (Köhl et al., 2023). Deforestation remained high into 2022 (around 500,000 ha that year as well), but by 2023 the annual clearing dropped to around 200,000 ha. This recent decline in deforestation may reflect stronger enforcement efforts and regulatory anticipation leading up to EUDR implementation. In short, Mato Grosso’s deforestation trend moved from a worrying surge to a significant reduction by 2023, which bodes well for future compliance if the trend holds.

Figure 3: Annual deforestation in Mato Grosso, 2013–2023. The bars show total area deforested each year (in thousands of hectares, “ha”). After moderate levels (~100–300 thousand ha) earlier in the decade, deforestation spiked to around 500,000 ha in 2022. A sharp decline is observed in 2023 (well under 200,000 ha), suggesting recent improvements in control measures.

Geographic Distribution of Deforestation

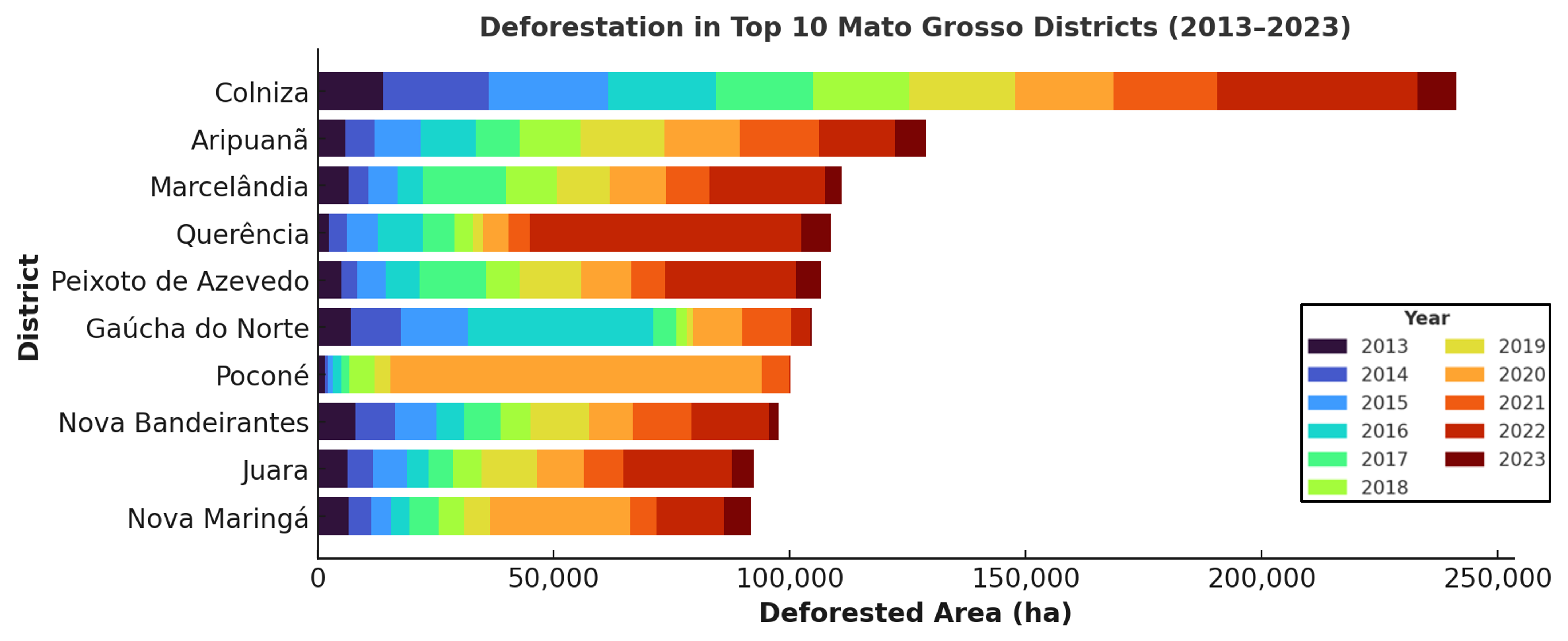

Deforestation linked to soy is not uniform across Mato Grosso. A small number of districts in the state’s northern and northwestern region account for a disproportionately large share of forest loss. For example, the districts of Colniza, Aripuanã, and Marcelândia each saw over 100,000 hectares of deforestation from 2013 to 2023, topping the list in forest clearing. Many of these top deforesting districts experienced notable spikes in particular years (such as Colniza in 2022, and Poconé with a large spike in 2020) as soy and other land uses expanded (see Figure 4). This means that enforcement and monitoring efforts may need to concentrate on a handful of hotspot regions, even though state-wide averages are improving. Overall, most other districts had much lower deforestation totals over the last decade, indicating the problem is concentrated rather than widespread.

Figure 4: Top 10 districts in Mato Grosso for deforestation (2013–2023), with breakdown by year. Each horizontal bar represents a district, ordered by total deforestation over the 11-year period. The length of the bar corresponds to total deforestation (ha), and colored segments show the contribution of each year (legend on right, 2013–2023). Colniza, Aripuanã, and Marcelândia (top bars) had the highest totals, each exceeding 100,000 ha of clearing. Colniza in particular shows a pronounced spike in 2022 (brown segment), and Poconé shows a very large spike in 2020 (teal segment). (Data source: TMF Deforestation Year for Mato Grosso).

Compliance Assessment

Soy Compliance Status

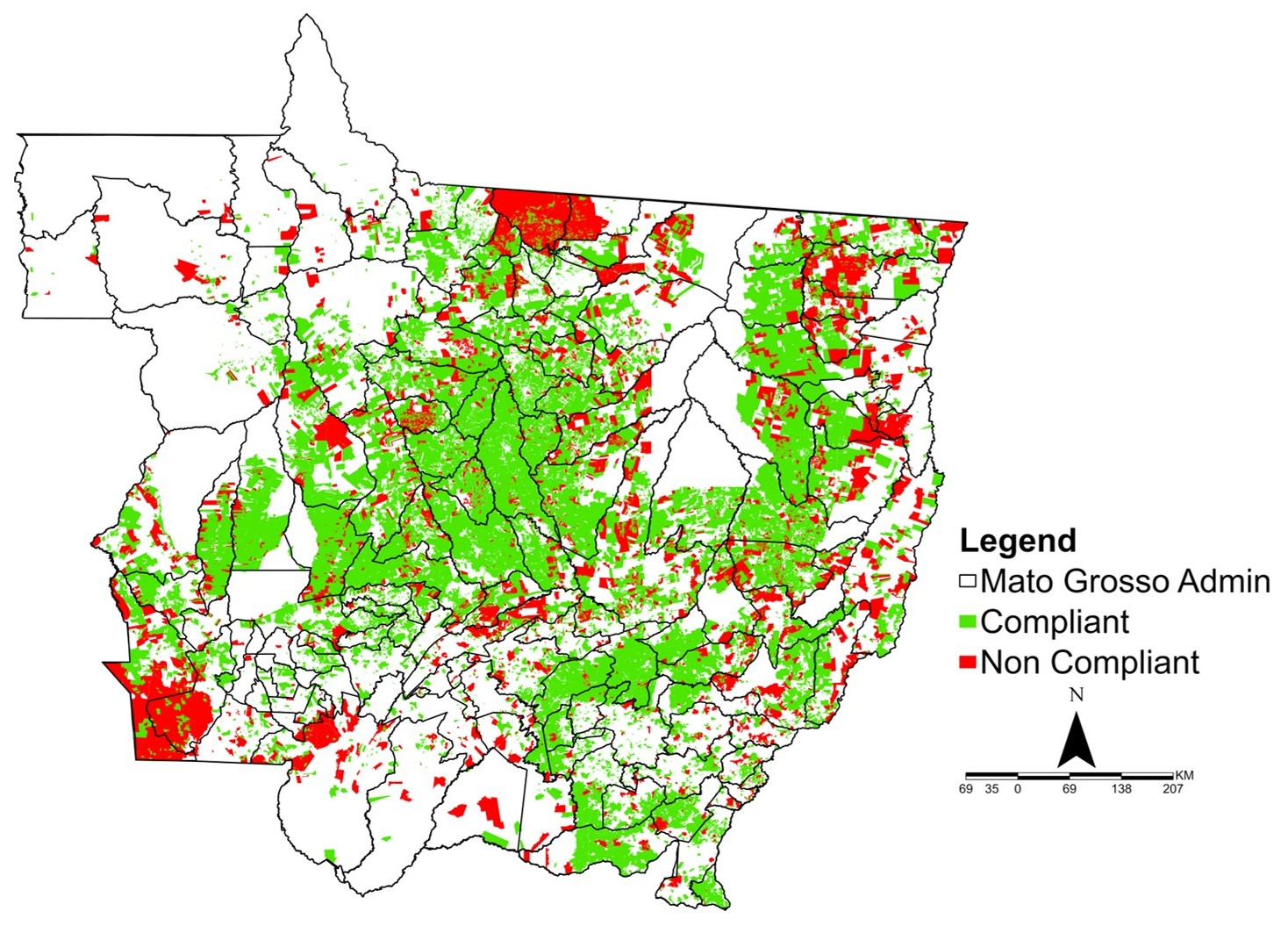

When we overlay all the criteria – deforestation cut-off, legal registration, and protected area exclusions – the analysis shows that the overwhelming majority of Mato Grosso’s current soy farmland meets EUDR compliance criteria (see Figure 5). Approximately 97.21% of the assessed soy plot area can be categorized as “compliant.” In practical terms, these compliant plots have not cleared any native vegetation after 2020 and they also did not fail the legal checks (they are properly registered and not farming inside a protected reserve). This finding is encouraging: it suggests most soy exported from Mato Grosso would be considered deforestation-free (post-2020) and legally produced, thereby meeting EUDR’s core requirements.

On the other hand, about 2.79% of the soy area was flagged as “non-compliant” by our assessment. These plots failed one or more of the criteria – typically either they showed evidence of deforestation after the cutoff date, or they were unregistered farms found within a protected forest area (an illegal situation). We examined this non-compliant subset to understand the main risk factors behind it.

Recent Deforestation

A number of the non-compliant plots had detectable forest clearing in the years 2021, 2022, or 2023. In fact, thousands of hectares were cleared across soy farms in those years – with the largest cleared areas being roughly 2,400 ha in 2021, 3,000 ha in 2022, and 2,400 ha in 2023. Any soy planted on land that was deforested in those years violates the EUDR cutoff, rendering those plots non-compliant. These cases likely represent farmers expanding their cultivation into forest areas or clearing portions of their legal reserves after 2020.

Land Legality and Protected Areas

The vast majority of soy-producing land in Mato Grosso appears to be legally compliant with respect to land tenure. Approximately 97.1% of the state’s soy cultivation area is officially registered in SNCI/SIGEF, indicating those farms have proper land title and environmental registration. Only about 2.9% of the soy area remains unregistered or of unclear legal status. We also found a few cases of soy encroachment into protected forests: soy plots overlapping Permanent Forest Reserves (PRFs) were identified in eight districts of Mato Grosso (ICMBio, 2023). These instances represent clear legal infringements, as farming is not allowed in those reserve areas. While the number of overlaps is limited, any soy coming from those plots would be automatically non-compliant due to illegal location. Aside from these isolated cases, however, most soy farms are operating on legally authorized land.

Protected Area Overlaps

We identified 36 soy plots that lie inside designated Permanent Forest Reserves (spread across the eight districts mentioned earlier). Soy from these areas is automatically non-compliant because the land itself is off-limits for agriculture. These instances are relatively rare, but each is a serious breach of land-use law.

Unregistered Farms in Protected Areas

A subset of non-compliant cases may involve plots that are both unregistered and in a protected area. Our criteria were somewhat conservative – if a plot was unregistered but not overlapping a protected area (and had no post-2020 deforestation), we did not immediately mark it as non-compliant. We assumed lack of registration alone (without other red flags) might not violate EUDR if the farm is otherwise legal and deforestation-free, since EUDR doesn’t explicitly mandate formal land titles but rather compliance with local laws. This cautious approach means the 2.79% non-compliant figure is likely a lower-bound estimate. If we had applied stricter rules (for example, considering any unregistered plot as non-compliant), the share of non-compliant soy area could rise to around ~5% of the total. We focused on the most clear-cut violations for this analysis.

Figure 5: EUDR Compliance Status of Soy Plots in Mato Grosso. The map displays the classification of soy cultivation areas based on deforestation and legal status. Green areas represent compliant plots with no post-2020 deforestation and valid land registration. Red areas are non-compliant due to either recent clearing or unclear tenure.

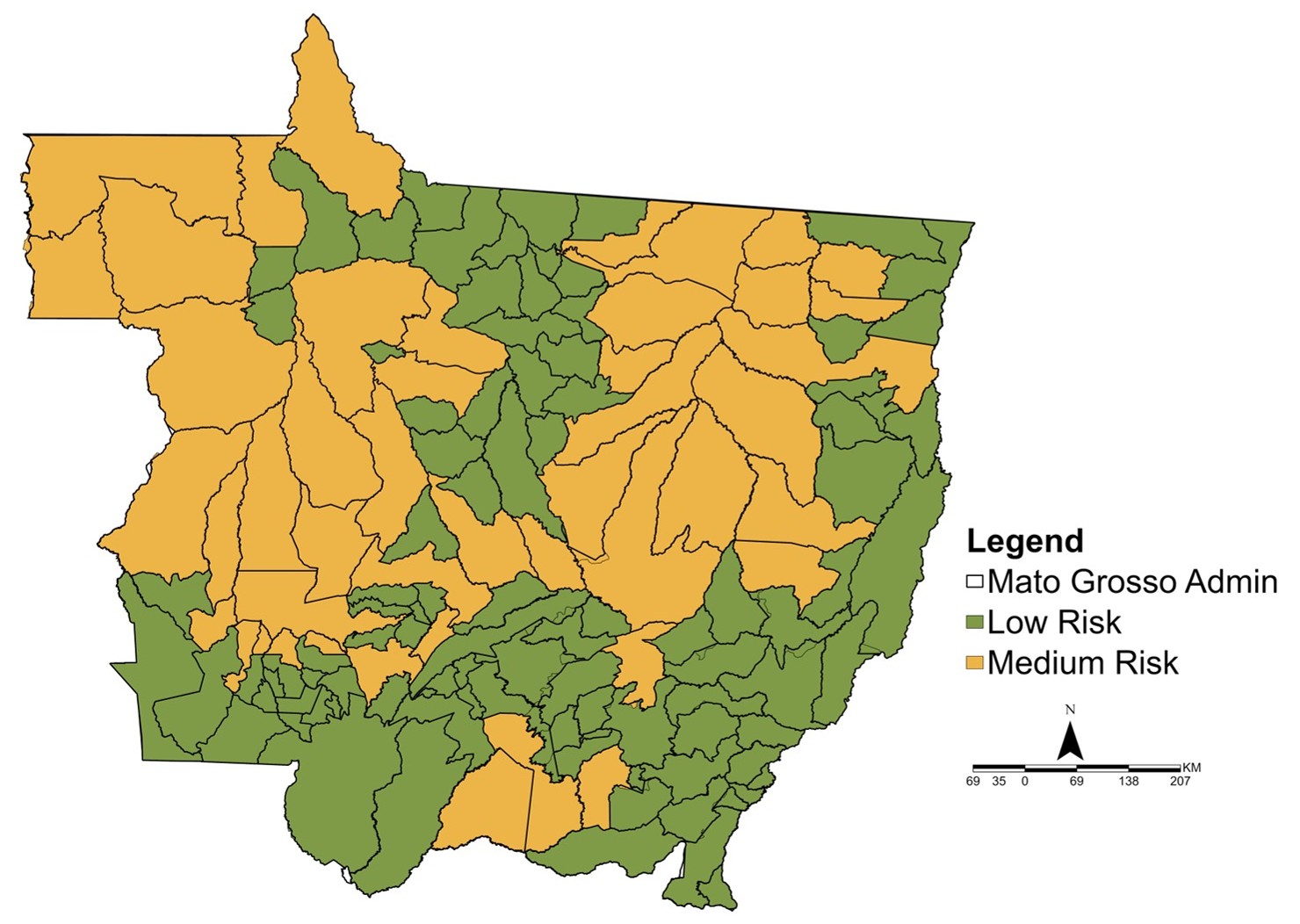

District-Level Risk Assessment

Beyond looking at individual farms, we also evaluated overall compliance risk by district (see Figure 6). Out of Mato Grosso’s 141 districts (municipalities), none were categorized as “High Risk” in aggregate, which is a positive sign. We classified 97 districts as Low Risk and 44 as Medium Risk for EUDR compliance. Even though no district was flagged as high risk, the Medium Risk category highlights where attention is needed. For example, certain districts like Porto Estrela have known cases of soy fields overlapping protected forests (hence some risk), and Colniza has a notable number of unregistered soy plots contributing to risk.

Additionally, major soybean production hubs such as Sorriso might carry traceability risks (mixing of soy from different farms at aggregation points). The Medium Risk areas are those with some red flags – be it recent deforestation, legal registration gaps, or proximity to remaining forests that could tempt future clearing. These areas will require enhanced due diligence and monitoring, even though they are not in outright violation at the moment. By contrast, the Low Risk districts show stable, compliant conditions with no significant deforestation after 2020 and strong legal adherence.

Figure 6: District-Level EUDR Risk Classification in Mato Grosso. The map categorizes the state’s 141 districts based on deforestation, legality, and traceability factors. Districts outlined in green are classified as Low Risk, while those in orange are Medium Risk.

Challenges and Opportunities

Implementing EUDR in the soy supply chain does pose several challenges that stakeholders must navigate:

- Traceability: Achieving full farm-to-port traceability for soy is difficult, yet it is crucial under EUDR. Soy supply chains often mix produce from many farms, making it hard to trace each batch back to its origin. Ensuring every shipment’s origin is known and verified as deforestation-free requires overhauling traditional commodity trading systems (WBCSD & Guidehouse, 2024).

- Legal Verification: Verifying that all soy is produced legally (in line with Brazilian environmental and land laws) demands rigorous and continuous monitoring of legal permits, environmental licenses, and land titles. Any changes in a farm’s legal status (e.g. a license expiring or a farm expanding into an unregistered area) could affect compliance (ABIOVE & APROSOJA, 2024). Keeping tabs on these aspects for thousands of farms is a significant administrative challenge.

- Continuous Monitoring: Even if a farm is compliant today, ongoing surveillance is needed to catch any new deforestation or encroachment that might occur. Regular satellite monitoring and alert systems are critical to detect deforestation in near-real-time and to ensure that no new illegal clearing goes unnoticed (DLA Piper, 2024). In a state as large as Mato Grosso, maintaining this continuous vigilance over millions of hectares is challenging.

On the other hand, EUDR also brings opportunities and benefits that can be leveraged:

- Transparency and Market Advantage: Complying with EUDR can push companies to improve supply chain transparency and documentation. In a market that increasingly demands sustainable products, this transparency can become a competitive advantage. Soy exporters who can prove their product is deforestation-free and legal may access premium markets and foster trust with buyers (WBCSD & Guidehouse, 2024).

- Technological Innovation: The stringent requirements spur innovation in monitoring and traceability tools. Advanced technologies like satellite imagery, AI-driven deforestation detection, blockchain for supply chain traceability, and big-data platforms are being adopted to improve accuracy and efficiency. These innovations not only help with EUDR compliance but also modernize agricultural supply chain management for the better.

- Alignment with Sustainability Goals: By enforcing no-deforestation and legality, EUDR compliance efforts align with broader environmental and sustainability goals. Strengthening land-use governance and protecting forests contribute to climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation. This alignment enhances Mato Grosso’s reputation as a responsible soy producer committed to sustainable development (Trase, 2020).

Role of Technology in EUDR Compliance

One promising avenue to tackle the above challenges is the deployment of dedicated technological solutions for monitoring and due diligence. For instance, MosaiX’s Agriplot Due-Diligence System (DDS) is a platform designed to help companies seamlessly comply with regulations like EUDR. Such a system provides end-to-end visibility and control over the supply chain by integrating various data streams. Key features of the Agriplot DDS include accurate geolocation of soy farms and real-time tracing of supply chains, automated compliance checks against deforestation alerts and protected area databases, and risk assessment tools that flag high-risk suppliers or regions in the chain. The platform can also generate standardized due-diligence reports to fulfill EUDR reporting requirements with ease.

Notably, systems like Agriplot DDS come with extensive global data coverage. In the case of MosaiX’s platform, it builds on a rich database of soy production worldwide (MosaiX, 2023). In Latin America alone, the system includes data on roughly 51.1 million hectares of soy fields and tracks operations of over 100 soy-related facilities across Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay. Additionally, it includes data on about 1.6 million hectares of soy plantations in Canada. This breadth of data enables cross-border analysis and benchmarking, which is valuable as traders source soy from multiple countries. A dedicated due diligence platform, hosted on secure servers, allows businesses to customize and privately manage their supply chain data. By leveraging such advanced tools, soy exporters and buyers can more efficiently achieve EUDR compliance, manage their deforestation and legality risks, and promote sustainability across their operations. In short, technology is acting as an enabler – turning a daunting compliance exercise into a more streamlined, data-driven process.

Summary of Findings

Our assessment of Mato Grosso’s soy supply chain reveals an overall positive outlook for EUDR compliance. Over 97.21% of the state’s soy-producing area already meets the EUDR criteria, meaning the vast majority of farms are deforestation-free (post-2020) and in adherence with Brazil’s legal requirements. This high rate of compliance indicates that most soy exporters in Mato Grosso are well-positioned to fulfill their due diligence obligations. Only a very small fraction of production – about 2.79% of the area – is flagged as potentially non-compliant or “at-risk” under the EUDR.

These non-compliant cases are concentrated in a few localized areas and are not representative of the state as a whole. The primary risk factors identified include post-2020 deforestation on certain farms, overlaps of soy fields with protected forests, and a handful of farms lacking proper registration. Importantly, no major region or municipality in Mato Grosso was categorized as “High Risk” for EUDR; the compliance issues tend to be isolated exceptions rather than widespread problems.

Overall, our findings highlight that EUDR-aligned production is already the norm in Mato Grosso’s soy sector. The small number of non-compliant cases can be addressed through targeted interventions, bringing the entire state’s production up to the required standard.

Conclusion

Mato Grosso’s soy supply chain appears largely prepared to meet the EU’s deforestation-free and legality standards. With well over 97.21% of soy area in compliance, the state stands as a strong example of how large- scale agriculture can align with strict environmental regulations. Addressing the remaining few percent of at-risk areas will be critical to achieve full compliance and maintain market access to the EU. Targeted actions should focus on the handful of problem cases identified – for instance, enforcing protections in zones where soy still encroaches on public forests, and accelerating land regularization for the few farms on unregistered properties. Strengthening on-the-ground enforcement (aided by enhanced alert verification systems like Inovasi Digital’s) and supporting farmers in rectifying any legal irregularities will help close the gaps.

By taking these steps, Mato Grosso can safeguard its vital EU export market and also solidify its reputation as a sustainable, deforestation-free soy producer. The case of Mato Grosso demonstrates that with robust data-driven monitoring and decisive enforcement, even a major agricultural frontier can achieve a high level of compliance with global anti-deforestation standards. This marriage of productivity with environmental compliance serves as an encouraging model for other regions. Moving forward, continued vigilance and innovation will ensure that Mato Grosso not only remains compliant with EUDR but also contributes positively to global sustainability goals.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for research and informational purposes only. It is not intended to serve as a legal basis for EUDR submissions or regulatory compliance.

References

- ABIOVE & APROSOJA. (2024).Impact of EUDR on Brazilian soy exports. FeedNavigator. Retrieved from https://www.feednavigator.com

- Council of the European Union. (2024). EU deforestation law: Council extends application timeline. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu

- DLA Piper. (2024). EU Deforestation Regulation implications. Retrieved from https://www.dlapiper.com

- ICMBio. (2023). National System of Conservation Units (SNUC). Retrieved from https:// www.icmbio.gov.br

- Köhl, M., Bourgoin, C., et al. (2023). JRC Global Forest Cover and Deforestation Dataset. European Commission, Joint Research Centre.

- MosaiX. (2023). Agriplot Due-Diligence System Features. Retrieved from https://mosaix.earth/solution/

- Reuters. (2023). Brazil soy output and trade statistics. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com

- Reuters. (2024). Brazil Supreme Court suspends Mato Grosso deforestation law. Retrieved from https:// www.reuters.com

- Trase. (2020). Soy and Deforestation Dynamics in Brazil. Retrieved from https://trase.earth

- WBCSD & Guidehouse. (2024). Understanding the EU Deforestation Regulation. Retrieved from https://www.wbcsd.org

MosaiX Article

MosaiX Article